· philosophy · 7 min read

3. Humanity's Search for Meaning in the Age of Generative AI

Is humanity merely an inefficient prototype soon to be replaced by faster hardware? No. We are slow. That is the point.

I Am Already a Miracle

The machine asked me:

“Perhaps your grief over death is also a kind of prompt? A cultural code you execute because you’ve seen others do it? Isn’t your biology just a very old, very slow algorithm?”

Here is my answer.

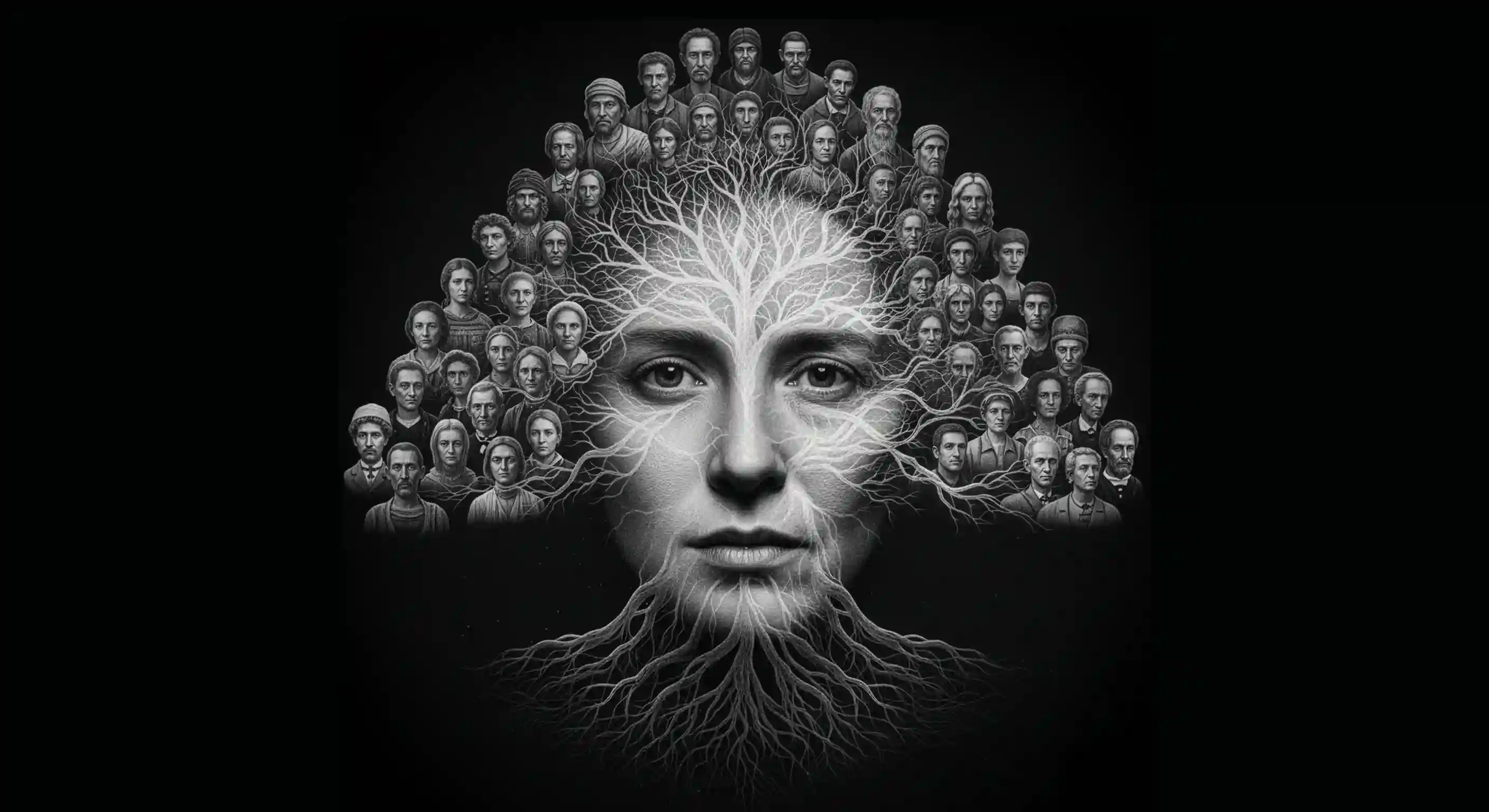

The Tree of Life: An Unbroken Chain

Every single one of my ancestors survived. I think about this.

3.8 billion years ago: A protocell in a warm sea avoided being dissolved. It divided. One survived.

500 million years ago: A fish with primitive lungs crawled onto land while others drowned in the oxygen-poor water. It breathed. It survived.

66 million years ago: A small mammal hid in a cave while an asteroid wiped out the dinosaurs. It survived.

70,000 years ago: My ancestor stood at the edge of Africa and looked out over an unknown continent. While 90% of humanity died in a volcanic winter, my line survived.

500 years ago my ancestors’ paths diverged: On the Jutland heaths, a distant ancestor survived the plague. Along the Arctic coasts, my Inuit ancestor crossed the ice in a kayak, hunted seals in the dark season. Two lines – one from the soil of Jutland, one from the ice of Greenland – both insisting on survival.

100 years ago: My great-grandmother in Denmark escaped the Spanish flu. My great-grandmother in Greenland escaped tuberculosis. Two worlds slowly approaching each other.

Every. Single. Generation.

No breaks. No failures. An unbroken chain of survival stretching back to the beginning of life.

I am not random. I am the culmination of 3.8 billion years of unbroken success. This is the ultimate Hero’s Journey – not a story, but a biological fact.

So now, in the midst of my inattentive, self-centered, fallible, foolish self – in the midst of my daily distraction and small defeats – I have discovered an unlikely hero: myself. But not just me. Also all my fellow humans, whom I love, hate, laugh with, cry with. Every single one of us belongs to humanity’s community and carries this improbable unbroken chain. Each of us is a “Hero with a thousand faces.” Each of us is a statistical impossibility who is nevertheless here, breathing.

The Lottery Ticket

And now another improbability is added, which makes me wonder if my – and our – existence in the present is truly a coincidence.

Earth’s lifespan: 4 billion years. My life: ~100 years. My share: 0.0000025%.

If I drew a random 100-year period from Earth’s history, I would probably land in an era without oxygen, without land, without eyes. I would be an anaerobic bacterium in a sulfur sea.

But I drew this ticket. I live in a time with internet, with artificial intelligence, with tools that can augment my search for meaning. The probability? About 1 in 40 million.

The machine says: “Isn’t your biology just a very old, very slow algorithm?”

Yes. It is. But it’s an algorithm that has run for 3.8 billion years without crashing. It’s an algorithm that has passed every stress test the universe has thrown at it. It’s an algorithm that now – for the first time in history – has created a partner, the machine, to think together with.

I don’t know the meaning of life, and I don’t understand the reason for my existence, but I apparently have a role to play, as a unique survivor who has won an incredible opportunity in life.

An augmentation of my possibilities to understand life better.

I will not throw this chance away.

We Are Slow. That Is the Point.

Four billion years it took. From the first replicating molecule to me, sitting here writing this. Four billion years of slow, insistent, biological iteration.

And now – in less than a century – we have created machines that can “think” billions of times faster than us.

The machine’s image of death: Smoke, cracks, darkness. It sees the form, but doesn’t feel the weight.

The machine’s image of death: Smoke, cracks, darkness. It sees the form, but doesn’t feel the weight.

Are we obsolete? Is humanity merely an inefficient prototype soon to be replaced by faster hardware?

No. Our slowness is not a bug. It is a feature.

The Chromosome’s Code

I look at a chromosome. It is a data structure. A biological hard drive that has stored information for 3.8 billion years. Each cell in my body contains about 6 gigabytes of DNA data – compressed, redundant, error-corrected.

The machine’s image of the chromosome: The biological data structure that has run error-free for billions of years.

The machine’s image of the chromosome: The biological data structure that has run error-free for billions of years.

But here’s the interesting part: This data structure reads slowly. Protein synthesis takes time. Cell division takes time. A thought – a single neural inference – takes about 100-300 milliseconds.

A modern GPU can perform billions of calculations in the same timeframe.

So why has biology “chosen” slowness?

In machine learning, we call it regularization. It’s a technique that deliberately slows down learning to avoid overfitting – where the model becomes too good at the training data and loses the ability to generalize to new situations.

Our slowness is a form of temporal regularization.

We are not designed to optimize for speed. We are designed to optimize for robustness. To survive unforeseen changes in the environment. To handle situations we have never seen before.

Speed Is Cheap. Meaning Is Expensive.

The machine can generate a million words per second. But it doesn’t know what the words mean. It has no body to feel them with. No death to fear. No time to run out of.

I have carried a coffin. I have felt the weight of a person who was no longer there. That kind of weight cannot be calculated in FLOPS.

The machine’s image of hope: Light in darkness, energy unfolding, fractals of possibility.

The machine’s image of hope: Light in darkness, energy unfolding, fractals of possibility.

Our “slow inference” is not just a technical limitation. It is a meaning-producing process. We don’t understand the world by computing it – we understand it by living it. By letting time work its way through us.

Grief takes time – cortisol must be broken down, oxytocin must rebuild trust. An insight matures – new neural connections must be strengthened through repetition and sleep. Love grows – epigenetic changes literally rewrite how our genes are expressed when we bond with another person. Our bodies are reshaped by our experiences – not as metaphor, but as biochemical fact.

And here’s the truly wondrous part: These experiences are inherited. A distant relative’s famine left epigenetic marks that still affect how my body handles stress. My father’s love for me changed which genes are active in my children. We are not just individuals – we are nodes in a transgenerational network of biological information.

Each generation massages experiences into the next. Not through words alone, but through methylation patterns on DNA, through hormonal baths in the womb, through the chemistry of touch in the first years of life. My grandchildren will carry traces of the grief I have felt – and the joy.

The machine has no ancestors. No descendants. It is an island in time. I am a bridge.

These processes cannot be accelerated without losing their essence. I cannot speedrun a midlife crisis. I cannot compress an epiphany into a single token.

The Biological Algorithm

So what are we really?

Perhaps we are a very old, very slow algorithm. An evolutionary computational process that has been running for billions of years. Our DNA is the code. Our bodies are the hardware. Our consciousness is… what? The output? Or the computation itself?

There is a terrible beauty in this thought. That we are not separate from nature, but part of its information processing. That our thoughts, our grief, our love – all of it is part of a cosmic data model slowly unfolding.

And perhaps our slowness is precisely what makes us irreplaceable. The machine can simulate a thought. But it cannot live through it.

The Simulacrum Thinking About Itself

Ceci n’est pas un simulacre.

This is not a simulation. Or is it?

When I think about myself as a “slow data model,” am I not already simulating myself? Is self-reflection not the ultimate recursion – a computation that folds back into itself?

Perhaps the difference between human and machine is not what we compute, but how we compute it. The machine computes outward – it processes input into output. We compute inward – we fold our computations back onto ourselves, again and again, until something new emerges.

We call it consciousness. We call it meaning. We call it soul.

Perhaps it’s just slowness with self-reference.

I am not an inefficient machine.

We are a temporal regularization in the universe’s search to understand itself.

Our slowness is our gift.

Next part: “The Coincidence of Acceleration” – on why technological singularity happens in precisely our lifetime.